In the Aftermath of Conversion Therapy, Counselors Offer Healing Support

In December 2014, a tractor-trailer traveling down Interstate 71 in Ohio struck and killed Leelah Alcorn.

Alcorn, who identified as transgender, had posted a suicide note on her Tumblr in which she described her isolation, desperation, and depression—feelings she blamed, in part, on the “conversion therapy” her conservative Christian parents forced her to undergo. Alcorn’s parents believed their “sick” child could be forcibly turned back into a boy and “cured” of her attraction to males.

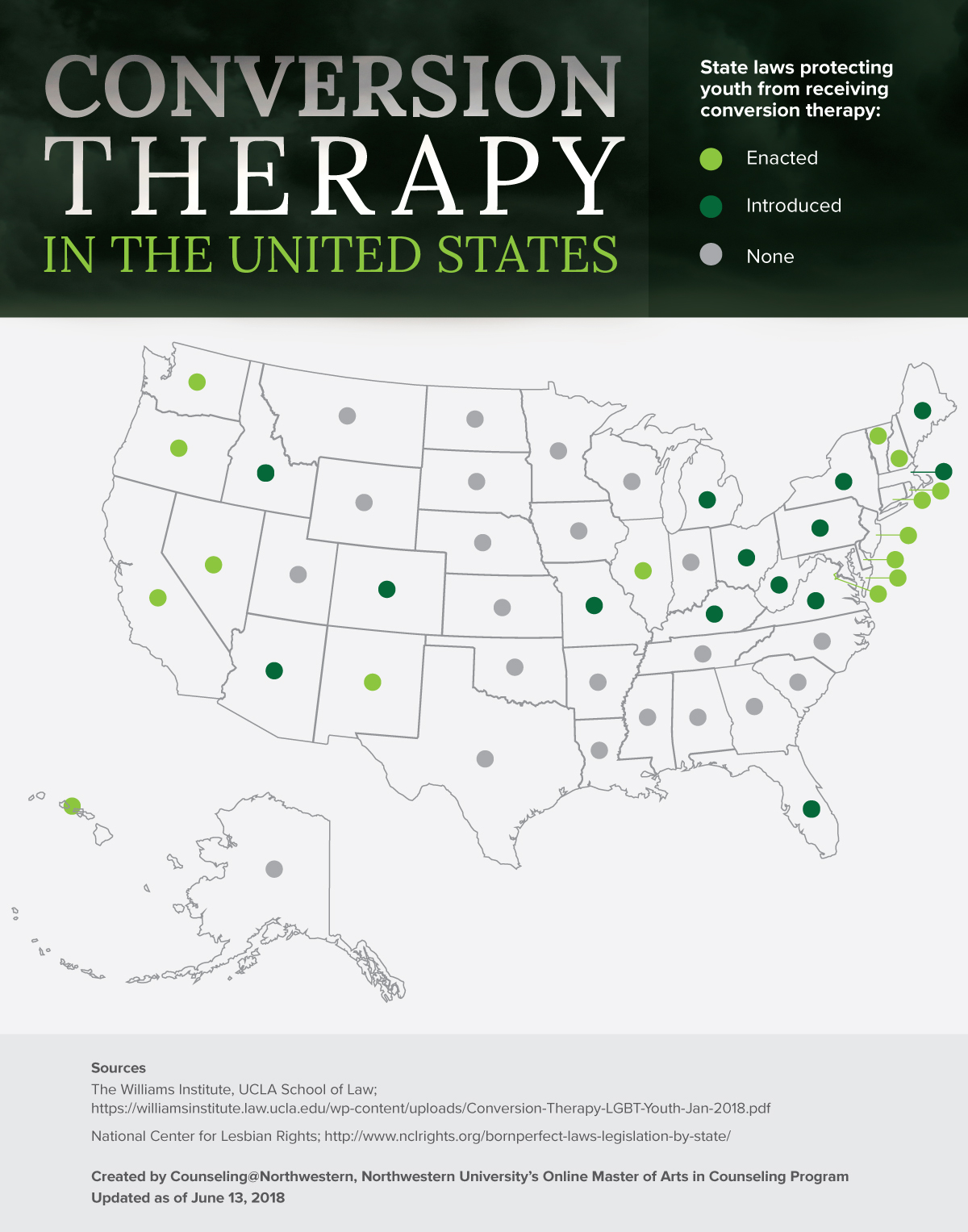

Alcorn’s death triggered international media attention. A little more than three months later, President Obama called for an end to conversion therapy and the White House issued a statement saying conversion therapy was potentially devastating to transgender, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and queer (LGBTQ) young people. Since then legislation has been introduced in many states across the country to ban the practice. Thirteen states and Washington, D.C., already have laws or regulations protecting minors from conversion therapy, also known as “reparative” and “ex-gay” therapy, and a movement is underway for a national ban.

View the text-only version of this graphic.

The Harmful Effects of Conversion Therapy

Discredited by the mainstream mental health community, including the American Counseling Association, American Psychological Association, and American Psychiatric Association, conversion therapy is viewed as ineffective, unscientific, and damaging.

“It’s trying to change the essence of the person,” said Dr. Joy Whitman, a licensed professional counselor with expertise on LGBTQ issues and core faculty member in the online Master of Arts in Counseling Program at The Family Institute at Northwestern University. “We know that sexual orientation can be fluid. But it’s the coercion to change that is the harmful nature of it. The basic communication is that there is something wrong with you if you are same-sex attracted.”

In a feature for Counseling Today co-authored by Dr. Whitman, the authors note that there is “no scientific evidence published in psychological peer-reviewed journals that conversion therapy is effective” and no “longitudinal studies conducted to follow the outcomes for those individuals who have engaged in this type of treatment.”

However, they point out that research consistently shows the harmful effects of the practice. Conversion therapy thwarts self-acceptance, causing depression, anxiety, shame, self-hatred, social withdrawal and, like Alcorn, thoughts of suicide.

“There’s a crisis of identities that’s involved here for clients and a potential loss of family. And there is a deep sense of shame born from religion, society, the educational and legal systems, and the mental health systems,” said Dr. Whitman. “Especially for kids, there is a sense of failure in not being able to change that can cause a loss of community and disconnect from family.”

Being unable to integrate their spiritual faith and sexual identity can lead to isolation, engagement in opposite-sex behavior as a way to assert a sexual identity, and intimacy issues. Dr. Whitman warns that without support systems to talk about safety, adolescents who grow up in these environments may engage in risky behaviors such as substance use. There is a documented potential for harm by engaging in the practice.

“It’s like saying a left-handed person should be right-handed. Being left-handed is not a disease,” said Scott Leibowitz, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and medical director of behavioral health for Nationwide Children’s Hospital’s THRIVE gender and sex development program. “You’re taking a non-pathological entity and applying a non-evidence-based intervention without considering the harm you’re doing along the way.”

A Shame-Based Practice

Yet some mental health professionals aligned with conservative religious groups continue attempting to convert gay and transgender people. And as bans on this practice gain traction amid the broader cultural shift embracing the LGBTQ community, pro-conversion therapy groups—and the conservative religious groups that support them—seem to be pushing back.

A new report by the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law projects 77,000 LGBT youth will undergo conversion attempts before they become adults. More troubling, many of the mental health practitioners attempting to “convert” their patients hold professional licenses, and conversion therapy for minors is still legal in the majority of states. (Indeed, some proponents of banning conversion therapy say the laws should characterize the practice as fraudulent. Currently, bans only apply to licensed therapies.)

The belief that LGBTQ people can be converted has roots in a rift that stretches back nearly 50 years. After protests by gay groups outside its annual conventions, the American Psychiatric Association reviewed its position that homosexuality should be treated as a psychiatric disorder. In 1973, it removed homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, saying it was no longer a sociopathic personality disorder. Two years later, the American Psychological Association agreed.

“Psychoanalysis was deservedly tarred with an antigay brush due to its pathologization of homosexuality and continued resistance to change until decades after the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association changed in the 1970s,” said Jack Drescher, a New York psychiatrist and author of Psychoanalytic Therapy and the Gay Man. “I think all the professions have done a turnaround so I don’t know if their reputations still suffer from that history.”

But the practice is still alive, if more difficult to identify. Professionals who engage in the practice often espouse “reparative therapy” and attempt to distinguish it from conversion therapy.

“Over time, clinicians are not necessarily defining themselves as conversion therapists. It’s more subtle and it’s become more deceptive and harmful,” said Leibowitz, who was not referring specifically to any one clinic or therapist. “These names of clinics sound reputable, and the families and youth are the unfortunate victims. They don’t know the stance of the clinicians, or the fact that the stance goes against professional ethical standards, which in my opinion is an abuse of power.”

Dr. Whitman explained how it can work.

“If I come to you and I say that I’m struggling with my sexual identity and my religious beliefs, some therapists say that they will help you with that conflict in a way where they can reduce your stress around your sexual orientation,” she explained. “So they might engage in some treatments that may not be specifically conversion therapy, but they may be reorienting you.”

There is less focus on changing the identity and more on redirecting the behavior and attraction, Dr. Whitman added. Both practices are basically the same, with a slight difference in the focus on behavior recognizing that the orientation is less malleable.

Regardless of whether it is referred to conversion therapy, reparative therapy or reorientation, many mental health practitioners argue that the practice starts from the wrong position, where a clinician enters into the work with a fixed assumption about the challenges the person faces and what the outcome should be.

“I look at the person as a blank slate,” Leibowitz said. “If I approach a person with depression under the belief that there is one aspect of them that needs to be changed in order to help treat their mood, I could be missing something else very important that truly needs to be addressed.”

Healing from Harm

An estimated 698,000 Americans have undergone conversion therapy, according to the Williams Institute, which means there are potentially hundreds of thousands of people damaged by the practice—many of whom have sought professional help to unravel the harm.

In the early years of his practice in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Drescher saw a number of gay men whose previous therapists had tried to change their sexual orientation.

“The advice on handling that is complex as there are many different reasons people sought to change, many kinds of therapists who tried to change them, and many different outcomes,” Drescher said.

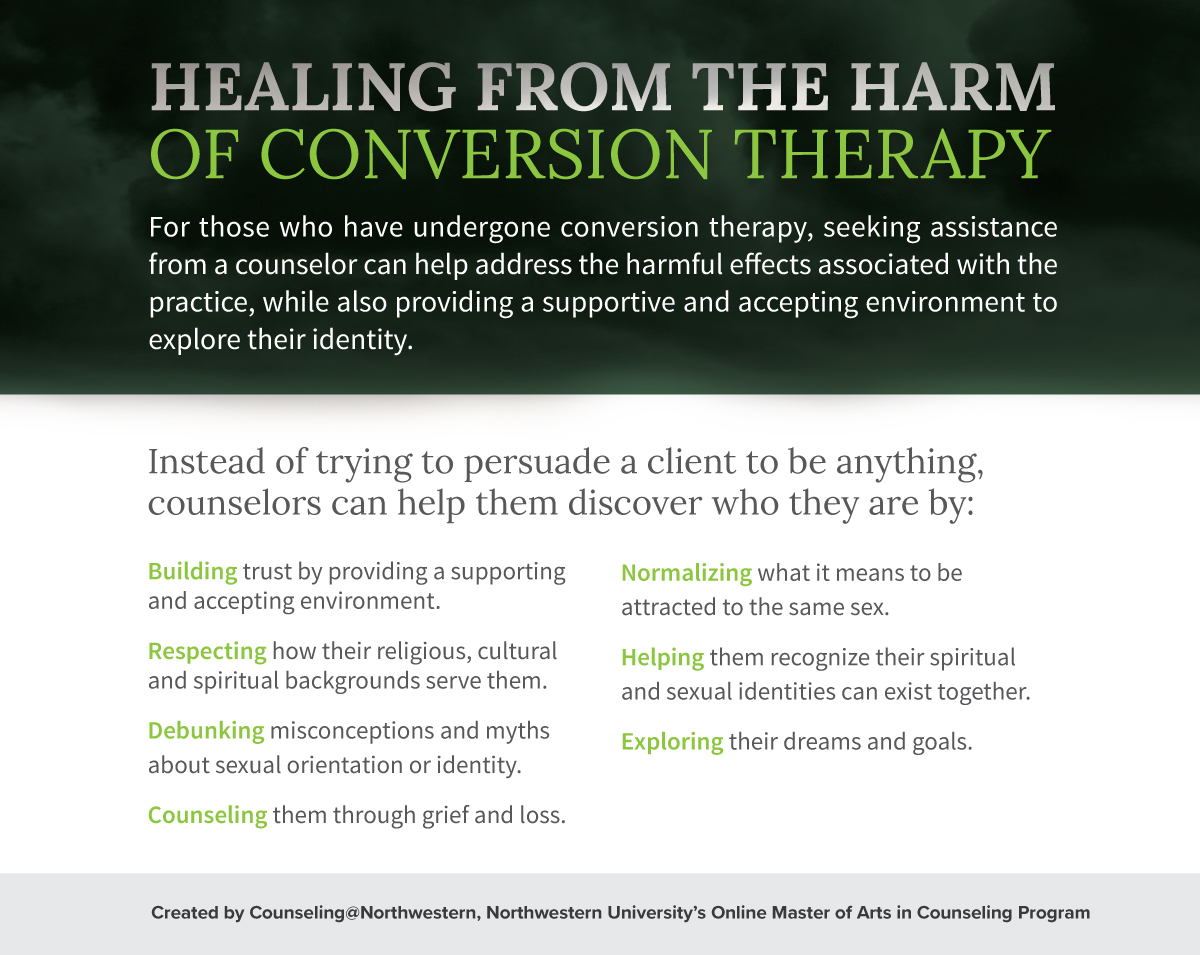

According to Dr. Whitman, a good place to start is to reestablish trust with a client seeking counseling.

“I have to remember that the very profession that I represent has betrayed them. They tried to get help from people that they thought were healers, so I’m very mindful that I will have to work hard to let them know that our work together will be supportive and that I want to understand the conflicts that they have,” she said. “My role with them is not to try to convince them to be anything, but to help them uncover and discover who they are.”

Dr. Whitman noted much of her counseling work in this realm has focused on normalizing same-sex attraction by breaking down myths and misconceptions about what it means to be same-sex attracted. Many people who attended conversion therapy were told they could not have a normal life if they acted on their attractions. Dr. Whitman said it is important to explore their dreams and aspirations and to show them their spiritual and sexual identities can exist together in a healthy, functioning way. Part of that may be helping them find faith-based communities that will support their sexual identities.

“In the past where those identities where dichotomized, I want to help them find a way to be whole,” Dr. Whitman said.

View the text-only version of this graphic.

She added that family members may also benefit from counseling.

“Families have their own dreams, expectations, and hopes for their family members and their children,” Dr. Whitman said. “You want to help them grieve the loss of the child that they thought they had and, instead, help them see the child that they do have.”

In addition to addressing their misconceptions about same-sex attraction, family members and parents may also benefit from connecting with other parents and families who have come from a greater place of affirmation, Dr. Whitman noted. Having support groups to lean on can help parents deal with their own unresolved feelings.

While some in the mental health and religious communities will continue to push this harmful practice, the mental health community, overall, has evolved and continues to evolve. With more education and training for mental health providers, Dr. Whitman believes the growing awareness of diversity along the spectrum of sexuality and gender will help stomp out the practice.

“There are some people that will never change their thinking and so for us our work is to go to those on the fence and to help them see the harm of trying to change somebody’s fundamental essence and to train them in affirmative practices.”

Connecting with LGBTQ Youth in Crisis

For more information about how to help LGBTQ youth and adults in crisis, consider visiting:

The Trevor Project: LGBTQ youth can call the free, 24/7 TrevorLifeline at 866-488-7386 to speak to a trained counselor.

LGBT National Help Center: LGBTQ individuals of all ages can receive peer-counseling by calling 888-843-4564.

Trans Lifeline: Transgender individuals in need of support can call 877-565-8860 to speak with volunteers who identify as trans and who are educated on the range of trans experiences within the community.

Crisis Text Line: Individuals in need of crisis support can text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor for free.

National Runaway Safeline: Youth and teens in crisis can call 1-800-786-2929 to speak with a trained volunteer who will listen, provide support and help determine next steps.

Citation for this content: Northwestern University’s Online Master’s in Counseling Program.